Review: Arizona Theatre Company’s ‘Pru Payne’ Shines a Light on the Complexities of Dementia

By M.V. Moorhead. Originally published by Phoenix Magazine.

“Keep your mind active.” We’re often told that this is a key to long term cognitive health: doing crossword puzzles or Sudoku or Wordle, reading, writing. But being a famous, award-winning critic and essayist hasn’t kept Prudence “Pru” Payne from one of the scourges of aging: dementia.

The title character of Arizona Theatre Company‘s Pru Payne is an aesthetic conservative. The dour, caustic Pru insists that the critic’s role is to defend high artistic standards; she advises her son, an aspiring novelist, never to settle for “good enough.”

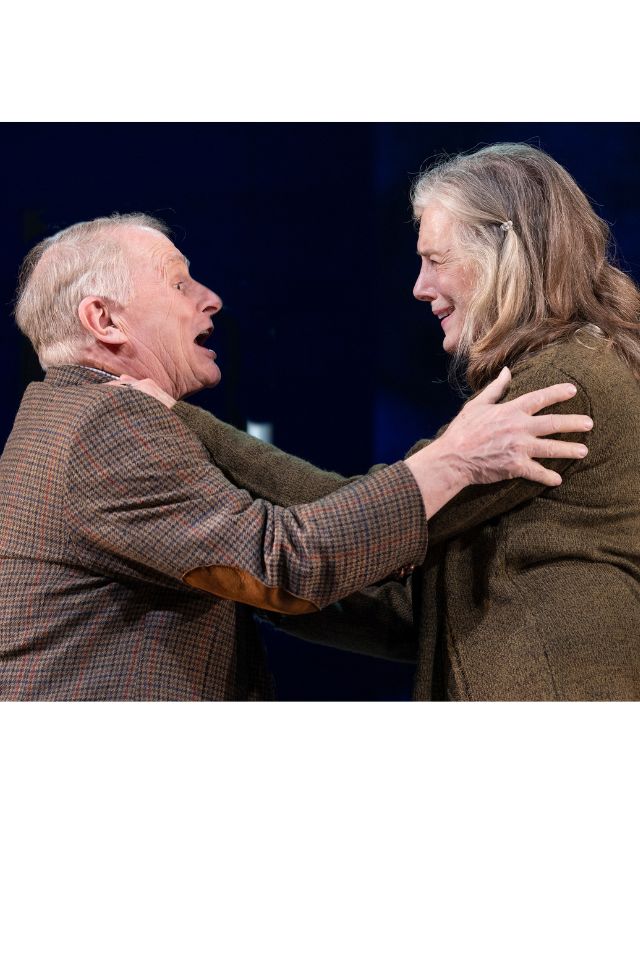

Her own memoirs are due, so it’s humbling indeed when she finds herself in a memory care facility near Boston. Yet despite her son’s assertion that his mother “doesn’t do love,” when Pru meets Gus, a friendly working-class fellow patient, the Radcliffe-educated intellectual takes to him without hesitation, breaking into an infatuated smile which he readily returns.

The story starts in 1988, allowing playwright Steven Drukman to explain terms like “sundowning” that weren’t as grimly familiar then as they are now. It also allows him some hindsight jokes, as when Pru laments that there’s a “B-movie actor” in the White House, but that this trend could get worse.

Pru is played by Mimi Kennedy, well known to rerun watchers for her many seasons on the sitcom Mom, and Gus is played by Gordon Clapp, longtime veteran of NYPD Blue. They make this odd coupling seem plausible; Gus is unintimidated by Pru’s bona fides, and his warmth and gallantry break down her defenses.

Kennedy creates a convincing portrait of a severe but not unlovable figure, hard-edged and self-impressed but observant and admirably invested in the world around her, and Clapp’s easygoing geniality offsets and complements her intensity. Tristan Turner and Greg Maraio do touching work as their respective sons.

Drukman’s structure is perhaps unsteady at times; at any rate it isn’t always clear if what we’re seeing is reality or Pru’s mind, and the character of the doctor (Veronika Duerr) wavers uncomfortably on the edge of caricature. Director Sean Daniels uses lots of abrupt sound cues and shifts in lighting — the impressively precise design is by Philip S. Rosenberg — as if to suggest Pru’s mercurial mental state. James J. Fenton’s spare but evocative setting is presided over by a huge, sectioned photograph of Pru’s face which fractures and sunders further as her disintegration progresses. It’s a potent effect.

Over the last decade or so, my late eldest sister gradually succumbed to dementia. Part of what I found so infuriating in this process was the sense of her brilliance and lifelong learning — she won three days on Jeopardy! — draining away. But Pru Payne seems to suggest that this is wasted anger. All intellect and accomplishment ultimately evaporates anyway, Drukman seems to say, but the loving connections that form between people, however different they may be, never do.